Frankly, the debate over the best konbini egg sandwich misses the entire point.

- Real mastery lies in strategic eating, using nutritional labels and seasonal cycles to your advantage.

- Success means navigating unspoken rituals for ordering hot food and using essential services like a local, not just grabbing the first thing you see.

Recommendation: Use this guide to move beyond being a tourist who just eats an egg sandwich and become a traveler who understands the entire konbini culinary ecosystem.

Let’s get one thing straight: the Japanese convenience store, or konbini, is the unsung hero of budget travel and late-night cravings. The internet is flooded with arguments over who makes the best tamago sando (egg sandwich). Is it 7-Eleven with its richer yolk, or Lawson with its pillowy shokupan? It’s a fun debate, but it’s the wrong question. Focusing on a single sandwich is like judging a Michelin-starred restaurant by its bread basket. It completely overlooks the complex, fascinating, and deeply satisfying culinary ecosystem operating under those fluorescent lights 24/7.

Most guides will give you a list of popular snacks. They’ll tell you that konbini are useful for more than just food, mentioning ATMs and ticket services. This is all true, but it’s superficial. It doesn’t teach you how to think like a local who relies on these stores for daily sustenance. The real key to unlocking the konbini’s potential isn’t about knowing *what* to buy, but *how* and *why* to buy it. It’s about a strategy that goes from deciphering nutrition labels for a balanced breakfast to mastering the unspoken rules of the standing noodle bar for a lightning-fast lunch.

Forget the simple comparisons. This guide is a food critic’s field manual. We’re going to deconstruct the entire system. We will move beyond the sandwich and explore how to build a genuinely balanced diet from the chilled aisles, understand the psychology behind the constant rotation of seasonal snacks, and learn the rituals for ordering everything from fried chicken to a steaming bowl of oden. By the end, you won’t just know which egg sandwich to try—you’ll have the confidence to navigate any konbini like a seasoned salaryman on their lunch break.

This article will guide you through the essential strategies and unwritten rules for mastering Japan’s konbini culture. Follow along to transform your convenience store runs from random snacking into a deliberate and delicious culinary experience.

Summary: A Critic’s Guide to Conquering the Konbini

- Healthy or processed: Can You Maintain a Balanced Diet on Konbini Food?

- ATM or Ticket Machine: What Services Can You Access at a Konbini?

- Sakura or Sweet Potato: Why You Must Try Seasonal Konbini Snacks?

- Is Loitering in the Konbini Parking Lot Acceptable at Night?

- Fried Chicken or Oden: How to Order Hot Food at the Counter?

- Soba or Udon: Which Noodle Should You Choose for Quick Energy?

- Eat and Walk: Is It Rude to Walk While Eating Street Food in Osaka?

- How to Order at Standing Noodle Bars Like a Salaryman

Healthy or processed: Can You Maintain a Balanced Diet on Konbini Food?

The first myth to bust is that a konbini diet is inherently unhealthy. Sure, you can load up on chips, sugary drinks, and instant noodles. But look closer, and you’ll find a complete, if compact, supermarket. The secret isn’t avoiding “processed” food—it’s about building a strategic plate. The Japanese concept of a balanced meal is built right into the offerings, you just need to know how to see it. Many of the core food groups evaluated in Japanese dietary health assessments, such as seafood, soy products, vegetables, and eggs, are all waiting for you.

Your best weapon is the nutrition label (栄養成分表示), usually found on the top left of the package. Don’t just look at calories (エネルギー). Focus on protein (たんぱく質) to ensure you’re getting something substantial. A typical strategy involves creating a “combo” meal: grab a salmon onigiri (rice ball) for carbs and fish protein, a small side of hijiki seaweed salad for fiber and minerals, and a hard-boiled egg or a small yogurt for an extra protein boost. This simple combination is far more balanced than a single, large pastry or a bag of chips. It’s not about finding a magical “healthy” item, but about assembling a complete, sensible meal from the available components. The famous acronym “Mago wa Yasashii” (grandchild is kind) is a mnemonic for a balanced Japanese diet, and you can build it right in the konbini: Ma (beans), Go (sesame), Wa (seaweed), Ya (vegetables), Sa (fish), Shi (mushrooms), and I (potatoes/tubers).

Your Action Plan: Building a Balanced Konbini Meal

- Calorie Check: First, check the calories (エネルギー/熱量) on labels to avoid unintentionally high-calorie items.

- Protein Hunt: Actively look for protein content (たんぱく質) in items like grilled chicken, tofu bars, eggs, and dairy products to ensure satiety.

- Full-Spectrum Scan: Locate the nutritional facts (栄養成分表示) to get a quick overview of protein, fat, and carbohydrates per serving.

- Combo Creation: Combine a main carb (like an onigiri) with a protein source (like a salad with chicken) and a vegetable side (like a small seaweed or edamame pouch).

- “Mago wa Yasashii” Audit: As you choose, mentally check off elements of the balanced diet acronym (beans, seeds, seaweed, vegetables, fish, mushrooms, tubers) to build a more diverse meal.

This approach transforms the konbini from a snack-and-go stop into a legitimate option for daily meals, provided you treat it like a grocery aisle and not a vending machine. It requires a bit more thought, but the payoff is a satisfying and surprisingly wholesome meal on a budget.

ATM or Ticket Machine: What Services Can You Access at a Konbini?

Thinking of the konbini as just a food destination is a rookie mistake. It’s the operational headquarters for daily life in Japan and an absolute lifeline for travelers. With over 56,000 convenience stores in Japan, you are never more than a few minutes away from solving a logistical problem. Most are open 24 hours a day, making them an incredibly reliable resource at any hour.

For international visitors, the most critical service is often the 7-Bank ATM found in 7-Eleven stores. They accept a wide range of foreign cards and offer an English-language interface, saving you from the panic of finding a compatible bank. But this is just the beginning. The multi-function kiosks, like Lawson’s “Loppi” or FamilyMart’s “FamiPort,” are powerful tools. These machines allow you to purchase tickets for everything from long-distance buses and museum exhibits to concerts and sporting events. They can seem intimidating, but a moment of patience (or a quick assist from the staff) unlocks a world of convenience.

This photo captures the moment a traveler interacts with one of these essential multi-service kiosks, the true command center of any konbini visit.

Beyond tickets, you can also use the konbini for practical travel needs. The Takuhaibin (luggage forwarding) service allows you to send your heavy suitcase directly to your next hotel, freeing you up to explore unencumbered. You can also print documents, photos, or e-tickets directly from a USB drive or your smartphone. Understanding these services transforms the konbini from a simple store into your personal travel assistant, streamlining your trip and solving problems before they arise.

Sakura or Sweet Potato: Why You Must Try Seasonal Konbini Snacks?

If you visit a konbini and only grab the standard, year-round items, you are missing the very soul of its culinary strategy: the relentless, brilliant cycle of seasonal and limited-edition products. This isn’t just about offering variety; it’s a deeply ingrained part of Japanese consumer culture that taps into a powerful appreciation for the transient nature of things. For a food enthusiast, this is where the real treasure hunt begins.

These limited-time offerings are a masterclass in marketing psychology. Take the humble strawberry. In Japan, strawberries have a dedicated season, and premium varieties can be astronomically expensive. Konbini leverage this cultural obsession perfectly. As Valentine’s Day approaches, you’ll suddenly find ichigo sando (strawberry sandwiches), often with added custard for an extra layer of luxury. This isn’t just a sandwich; it’s a small, affordable taste of a seasonal celebration, creating a sense of urgency and a “now-or-never” appeal that is incredibly effective. This cycle repeats throughout the year, offering a constantly changing menu that reflects the season.

To navigate this delicious calendar, it helps to know what to expect. This table breaks down the typical flavor profiles and products you’ll encounter as the seasons change, each tied to a specific cultural moment.

| Season | Featured Flavors | Product Examples | Cultural Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | Sakura (Cherry Blossom) | Sakura mochi, Pink beverages | Hanami celebration |

| Summer | Melon, Citrus | Melon bread, Yuzu drinks | Refreshing heat relief |

| Autumn | Sweet Potato, Chestnut | Yakiimo desserts, Kuri dorayaki | Harvest appreciation |

| Winter | Strawberry, Chocolate | Ichigo sandwiches, Hot chocolate | Valentine’s/White Day |

Hunting for these seasonal items transforms every konbini visit into a potential discovery. It encourages you to step outside your comfort zone and try a sakura-flavored latte or a sweet potato-filled pastry. It’s the easiest way to connect with the rhythm of Japanese culture and a guaranteed way to find your new favorite snack—one that might be gone by your next visit.

Is Loitering in the Konbini Parking Lot Acceptable at Night?

You’ve secured your meal, a perfect combination of onigiri, salad, and maybe a piece of fried chicken. Now what? This is where many travelers face a moment of uncertainty. Japan’s public etiquette, particularly around cleanliness and consideration for others, can make the simple act of eating feel fraught with rules. The image of young people hanging out in konbini parking lots at night might suggest it’s a free-for-all, but the reality is more nuanced.

The primary rule is simple: be clean and be considerate. While it’s generally not a major faux pas to eat in your car, the key is to leave no trace. Every konbini has trash and recycling bins, usually near the entrance. You are expected to use them and, crucially, to separate your garbage correctly into plastics, burnables, and cans/bottles. Lingering for an extended period, making noise, or occupying prime parking spots can be seen as inconsiderate, especially at busy locations.

A growing number of newer, larger konbini have addressed this issue directly by installing “eat-in” spaces. These small areas with a few tables, chairs, and often a microwave and hot water dispenser, are your best bet. They are designated for consumption, so you can relax and eat without worrying about breaking any unwritten social rules. If an eat-in space isn’t available, the next best option is to find a nearby public park or bench. This is a far more socially acceptable location to enjoy your meal than standing directly in front of the store, where you might block the entrance for other customers.

Fried Chicken or Oden: How to Order Hot Food at the Counter?

Graduating from the chilled aisles to the hot food counter is a major step in your konbini journey. This is where you find some of the most satisfying and iconic cheap eats, from crispy fried chicken to the complex, simmering world of oden. But for a first-timer, the process can be intimidating. The staff are often busy, and the ordering process relies on a few key phrases and gestures.

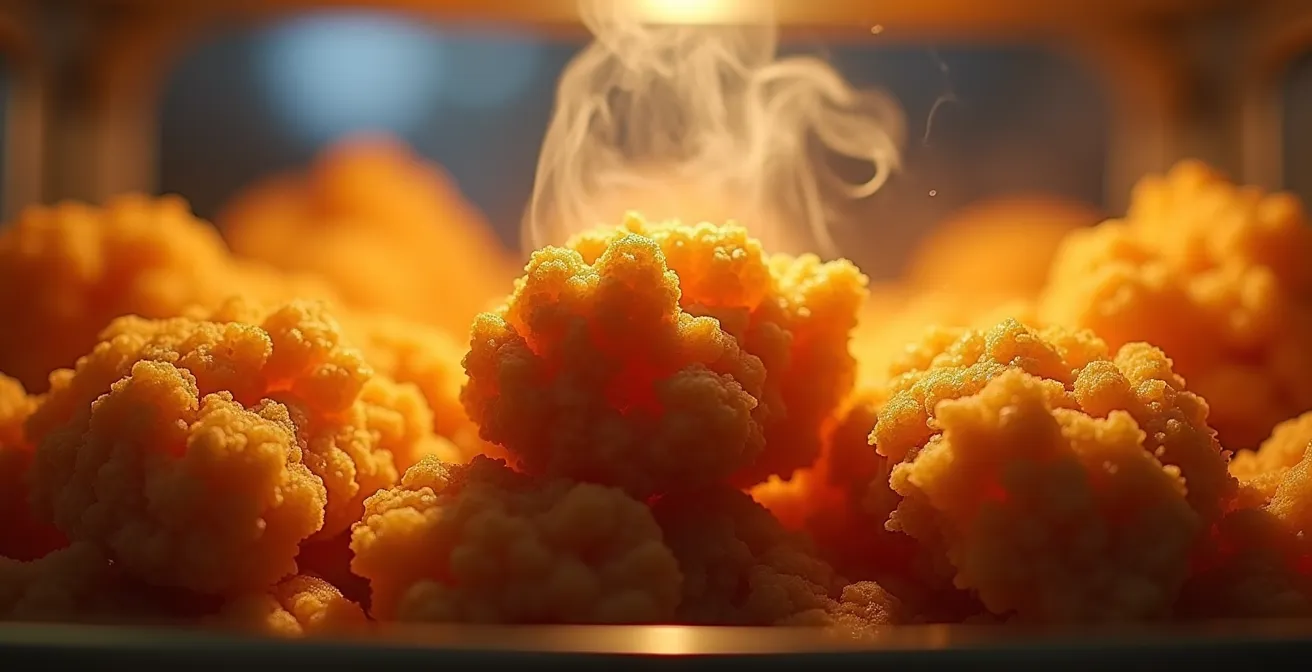

The most famous offering is the fried chicken. Each chain has its own signature brand: FamiChiki at FamilyMart, NanaChiki at 7-Eleven, and Karaage-kun (nugget-style) at Lawson. The chicken sits in a heated glass case near the register. The simplest way to order is to point and say, “Kore kudasai” (This, please). If you want the freshest possible piece, you can try asking, “Age-tate wa arimasu ka?” (Are there any freshly fried ones?).

This up-close view shows the golden, crispy texture that makes konbini fried chicken an irresistible, must-try hot snack.

Oden, the wintertime favorite, is a bit more complex. It’s a self-service or staff-assisted affair where you choose from various items like daikon radish, tofu, and fish cakes simmering in a savory dashi broth. You grab a cup, select your items, and then take it to the counter. Don’t forget to ask for the broth by saying, “Dashi mo onegaishimasu” (Broth as well, please). Near the oden station, you’ll find small packets of karashi (spicy Japanese mustard), the traditional condiment that cuts through the rich flavors perfectly. Mastering the hot counter is a ritual, and a little preparation makes it a smooth and deeply rewarding experience.

Soba or Udon: Which Noodle Should You Choose for Quick Energy?

When you need more than a snack, the noodle section offers a substantial and incredibly affordable meal. The two titans of the chilled case are soba and udon. While they might look similar—both are noodles in a savory broth—they serve different purposes in your strategic fueling plan. As a discerning eater, choosing the right one depends on the kind of energy you need for the day ahead.

Your choice comes down to the core ingredient. Udon noodles are thick, chewy, and made from wheat flour. They are the ultimate comfort food, especially in winter when served hot. Because they are made from refined wheat, they have a higher glycemic index, meaning they provide a quick burst of energy. This makes them a great choice if you need an immediate pick-me-up before an afternoon of walking. Soba noodles, on the other hand, are made from buckwheat flour. They are thinner, have a nuttier flavor, and a firmer texture. Critically, as nutritional research indicates soba has a lower glycemic index. This means they release energy more slowly, providing sustained fuel that can help you avoid a post-lunch crash. This makes soba, especially cold zaru-soba in the summer, an excellent choice for long-lasting energy.

This comparison from a recent nutritional analysis highlights the key differences to help guide your decision based on your energy needs and taste preference.

| Characteristic | Soba (Buckwheat) | Udon (Wheat) |

|---|---|---|

| Glycemic Index | Lower (sustained energy) | Higher (quick energy) |

| Best Season | Summer (cold zaru-soba) | Winter (hot kake-udon) |

| Protein Content | Higher | Moderate |

| Texture | Nutty, firm | Chewy, soft |

| Calories per serving | ~280 kcal | ~320 kcal |

Understanding this fundamental difference allows you to use the konbini noodle aisle strategically. Are you looking for a quick, comforting carb load? Go for udon. Do you need steady energy for a long day of sightseeing? Soba is your best friend. It’s another layer of mastery that elevates your konbini run from a random purchase to a calculated culinary choice.

Eat and Walk: Is It Rude to Walk While Eating Street Food in Osaka?

The “no eating while walking” rule is one of the most well-known pieces of Japanese etiquette advice given to travelers. It generally stems from a cultural emphasis on cleanliness and avoiding the inconvenience of dropping food or needing to dispose of trash in a country with few public bins. For the most part, this is sound advice. You will rarely see locals walking down a typical street while eating.

However, as with many rules in Japan, context is everything. The rule is not absolute, and certain situations and locations provide clear exceptions. During a festival, or matsuri, the streets are crowded with people buying food from stalls, and eating while slowly moving with the crowd is perfectly acceptable. Similarly, in major tourist-heavy food districts like Dotonbori in Osaka or Nakamise-dori in Asakusa, the rule is heavily relaxed. The entire purpose of these areas is to sample food from various vendors.

The type of food also matters. A katsu sando or an onigiri from a konbini is designed for on-the-go consumption. While it’s still most polite to stop and eat it discreetly to the side or in a park, it’s not considered a major offense to eat it while walking if you’re in a hurry. In contrast, food from a traditional street vendor, like takoyaki or yakitori, comes with a different expectation. These vendors almost always have a small, designated standing area where customers are expected to finish their food and return the trash directly to the vendor. This is a critical distinction: konbini food is portable by design; vendor food is hyperlocal.

Key Takeaways

- The konbini is a complete culinary ecosystem, not just a snack shop. Mastery requires strategy, not just knowing the most popular items.

- Balance is achievable by combining items: pair a carb (onigiri) with protein (chicken/tofu) and vegetables (seaweed salad).

- Leverage the full range of services, from ATMs and ticket kiosks to luggage forwarding, to make the konbini your travel command center.

How to Order at Standing Noodle Bars Like a Salaryman

You’ve mastered the onigiri, you can order fried chicken without hesitation, and you know the difference between soba and udon. It’s time for the final exam: the standing noodle bar, or tachi-gui soba. These tiny, efficient eateries, often found in or near train stations, are the domain of the salaryman in a hurry. They are the epitome of fast, cheap, and delicious food, and blending in requires knowing the protocol.

The entire process is built for speed, especially during the lunch rush when a significant portion of the 22 million daily convenience store visitors are looking for a quick meal. The first and most important step happens before you even speak to a person. Look for the ticket machine (券売機) near the entrance. You insert your money first, then press the button for your desired dish. You can often choose your noodle type (soba or udon) and add toppings or a large portion (大盛り). Once the machine spits out your ticket, you hand it to the staff behind the counter and find an open spot.

Your bowl will be ready in a minute or two. Now it’s time to customize. On the counter, you’ll find an array of free condiments. The essentials are shichimi togarashi (a seven-spice blend), tenkasu (crunchy tempura flakes), and beni shoga (pickled ginger). Add them to your liking. And yes, you should slurp your noodles loudly. It’s not rude; it cools the noodles and is considered a sign of appreciation. Once you’re finished, don’t just leave your tray on the counter. Look for the designated return shelf (返却口) and place your empty bowl and tray there. Following this simple salaryman protocol allows you to navigate these fantastic establishments with the quiet confidence of a local.

So stop debating and start eating. The egg sandwich was just the beginning. Your next perfect, cheap Japanese meal is waiting under the fluorescent lights, whether it’s a seasonal pastry, a bowl of oden, or a quick plate of noodles. The only question is what you’ll discover first.

Frequently Asked Questions on Konbini Etiquette

Why is eating while walking considered rude?

It relates to a cultural emphasis on cleanliness and the general scarcity of public trash cans. Japanese society places a high value on not creating a mess or causing potential inconvenience for others, and eating on the move increases the risk of spills or litter.

Are there exceptions to this rule?

Yes, the rule is highly context-dependent. It is generally relaxed during festivals (matsuri), in busy, food-focused tourist areas like Dotonbori in Osaka, and within large parks where picnicking is a common and accepted activity.

What should I do if I buy street food?

The most polite approach is to look for a designated standing or sitting area near the vendor. Eat your food there, and then return any disposable trays or skewers directly to the vendor, as they will have the appropriate system for disposal.